April 25 – April 29, 2018

Flexspace C, CICA Museum

Statement

I’m from a middle-class family where my parents both worked full-time and raised me in front of a television, so most of my memory either good or bad comes from it. In the age of analog cameras, record players, cassette tapes and black-and-white television before the advent of computer games, digital gadgets, mobile phones or social network, buying a two-for-one movie ticket was the best entertainment I could find once in a blue moon.

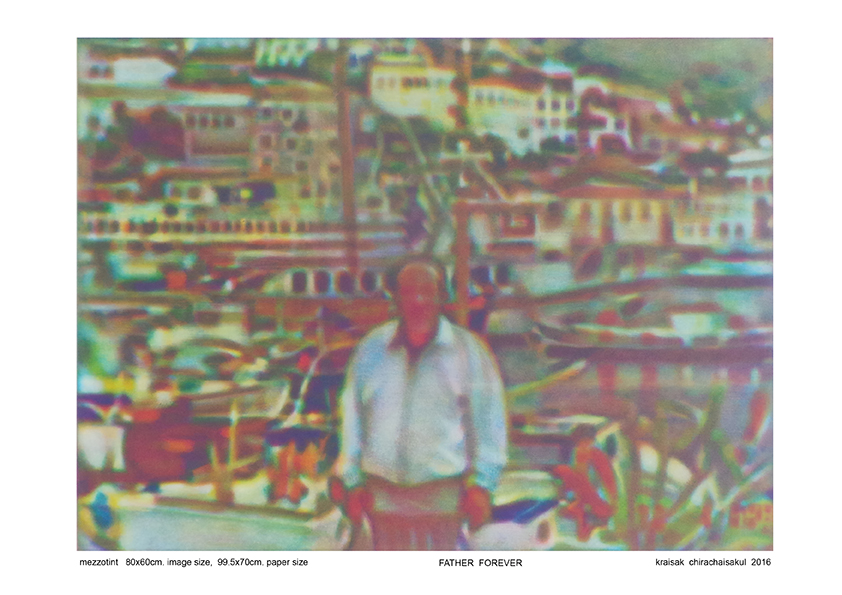

After producing realistic printmaking for ages, my years of experience are dedicated in this collection under the name “THE MISSING MEMORIES”, which presents views from different life experiences including childhood memory. To lower the realism and clarity shows the process of remembering and forgetting at the same time. This is similar to when we look at the horizon, we can’t pinpoint if it’s a sunrise or sunset. That is, while we feel like we recall something, we seem to somewhat forget it.

Whoever that was born during my time might be able to recognize what we used to know or see, know where we were at the time or even what we were doing. Then we feel the sense of empathy, happiness, grief, sadness or even appreciation. These different emotions can return to haunt us. More or less depends on their experiences but this is how I have my recollection, which is derived from watching TV. Certainly, once the time has passed, I will need to use new media, such as a computer to trace back and confirms this fuzzy story.

At 52, Kraisak Chirachaisakul is making up for lost time. After distancing himself from the art world for almost three decades, following his graduation from Silpakorn University back in 1987, the winner of this year’s Gold Prize at the International Biennale Print Exhibition in Taiwan is staging a comeback.

“I don’t know how they picked the winner. Maybe they counted the number of heads included in each print,” Kraisak jokes. He is casually dressed, bearded, slightly pot-bellied. An image of Chinese contemporary artist Ai Weiwei comes to mind.

Kraisak’s winning piece, The Greatest Love, is an 80 x 60cm mezzotint print depicting a veritable sea of heads, a crowd of well over a thousand people waving flags to salute HM the King. He has playfully included a Furby doll in the work, as if viewers could join in the

search for Waldo. It took him about three months to complete the print, he tells me.

Mezzotint is an age-old printmaking process, a child of the intaglio family, where a range of tones and fine details are produced by burnishing the surface of a metal plate, usually made of copper.

Having mastered an elaborate technique that’s capable of yielding stunningly detailed results, Kraisak is enthusiastic about explaining the procedures involved. He pulls up a YouTube video made by a good friend of his, who begins the process by sharpening a metal tool called a rocker; this is used to create crosshatches on the surface of a metal plate prior to any details being added.

“The practice of printmaking, as we know it today, didn’t begin as an art form,” Kraisak notes, speaking over the video. “It began as a way of making copies of great paintings. An artist could spend a whole year creating a large painting and before selling this to a client he would hire a printmaker to make a reproduction of the work so that he would have a copy to keep for himself.”

It was only much later, when people began recognising that printmakers were capable of creating certain aesthetic effects that couldn’t be achieved by painters — such as tonal contrasts or shades produced by the superimposition of colours — that printmaking came to be viewed as an art form in itself.

Kraisak learned the mezzotint technique from Kamol Sriwichainan, now a much-respected local artist, when both of them were still studying at university. “You know, taking a photograph is a great deal quicker,” Kraisak quips.

When he graduated from Silpakorn, however, he decided to take a different path from that followed by many of his artist peers, people like Kamin Lertchaiprasert. “I didn’t think I could earn a living from making prints,” he explains. “I was young so I decided to get a conventional job and have a family like everyone else,” he recalls. “I chose to go to art school because I was playing it safe by opting to study what I was best at. If I were smarter, I might have studied to become a doctor or taken some other difficult course. But I chose something that was easy for me.” He found work at an advertising agency and later opened his own shop selling model toys in what used to be the World Trade Centre building in Bangkok. But, in a way, he never really did give up the practice of art. He used to create his own models for sale and was fond of making human figurines, moulding the arms and legs, filing and smoothening out the surfaces, sculpting the faces.

“I’ve always been fascinated with faces. Ever since I was a child I used to like comparing people’s facial features. If you let me judge a beauty pageant, I could pick the most beautiful contestant,” he enthuses. “Once, when I still a kid, I saw a pretty woman on a bus who was pregnant but I couldn’t understand why she had a belly like that, what the reason for the wide range of variations in human features was. Not that I have any greater understanding of that even now.” After the World Trade Centre was set on fire during the street demonstrations of 2010 and large sections of it were badly damaged, Kraisak remembers feeling pretty hopeless about his future prospects. “I had a certain set of skills and I didn’t know how to do any other kind of work,” he recalls. “So I decided to start making art again after a hiatus of 20 years.”

That his works centre on images of the current monarch is potentially fraught with political implications. But his explanation for this focus is disarmingly simple: “When I started drawing again, I wanted my work to have some significance. I like drawing people and who is more significant than HM the King?”

His prints are not conventional portraits of the monarch, however, not the sort of image that Thais might hang on a wall in their homes or use as the centrepiece for a shrine; they are often portrayals of large crowds showing their respect and love for the King, the perspective being what His Majesty himself might see when he makes an appearance before a large public gathering.

Since Kraisak got back into making prints, he says he’s been spending most of his waking hours working on new mezzotints. “Maybe it’s a bit like praying, don’t you think? Like when you pray and you have to say a prayer a hundred times in order to get that sense of completion. I draw heads, heads, heads… of people smiling at the King, of people at public gatherings,” he says. “It helps me cope.”

Printmaking still isn’t a particularly profitable activity, but now Kraisak is purely motivated by his love for the medium. He says he submits work of his to various art competitions in order to gauge the level of mastery he is achieving. Last year, he won an award for excellence at the Awagami International Miniature Print Exhibition in Japan, as well as the grand prix at the 8th Biennale Internationale d’Estampe Contemporaine de Trois Rivieres in Canada. He also put on a solo show at Bangkok’s Numthong Gallery towards the end of last year.

“I’m doing new work all the time now,” he says, “I’m old and I’m starting to feel like I want to leave something behind [for posterity]. I feel like I’m the only one that’s old.”